AI Or Die

In May of 2017, I founded one of the first autonomous robot fighting competitions. It grew to around 10 people at its peak. This is a medium-level overview of the project.

Note: This is an article I posted a while back, updated for new media coverage at the end.

Fresh-faced and straight out of college with a burning desire to do something cool, I started going to an awesome meetup in Oakland called DIY Robocars. At this meetup, people build their own small autonomous vehicles and race them around a track. I met some really cool people there, including the people that started the Donkey Car project, a woman who builds cocktail-making robots, and, most of all, Mike Winter, or “Robot Mike” as he loves to be called. Mike told me about his and his daughter Lisa’s time on the TV show Battlebots, and all of the cool projects he’s worked on (his website is a bit out of date but does show some of the things he’s worked on). Mike told me about this idea he’s had for years — Take the battlebots that he and Lisa have been building and put some sensors and a brain inside. They needed to be fast. The slow robots that have been seen at the DARPA challenges or other combat robot competitions wouldn’t do. They need to have flashing lights to look good for TV and they need to have personality.

I was sold. I told Mike I wanted to be a part of the project, and quit applying for jobs, and took on the last loans I could take out of college. The summer of 2017 I spent almost every day working on autonomous battle robots, learning everything from 6 ways to not install ubuntu to how to get a neural network working on a real battlebot.

Step one: Get a robot moving

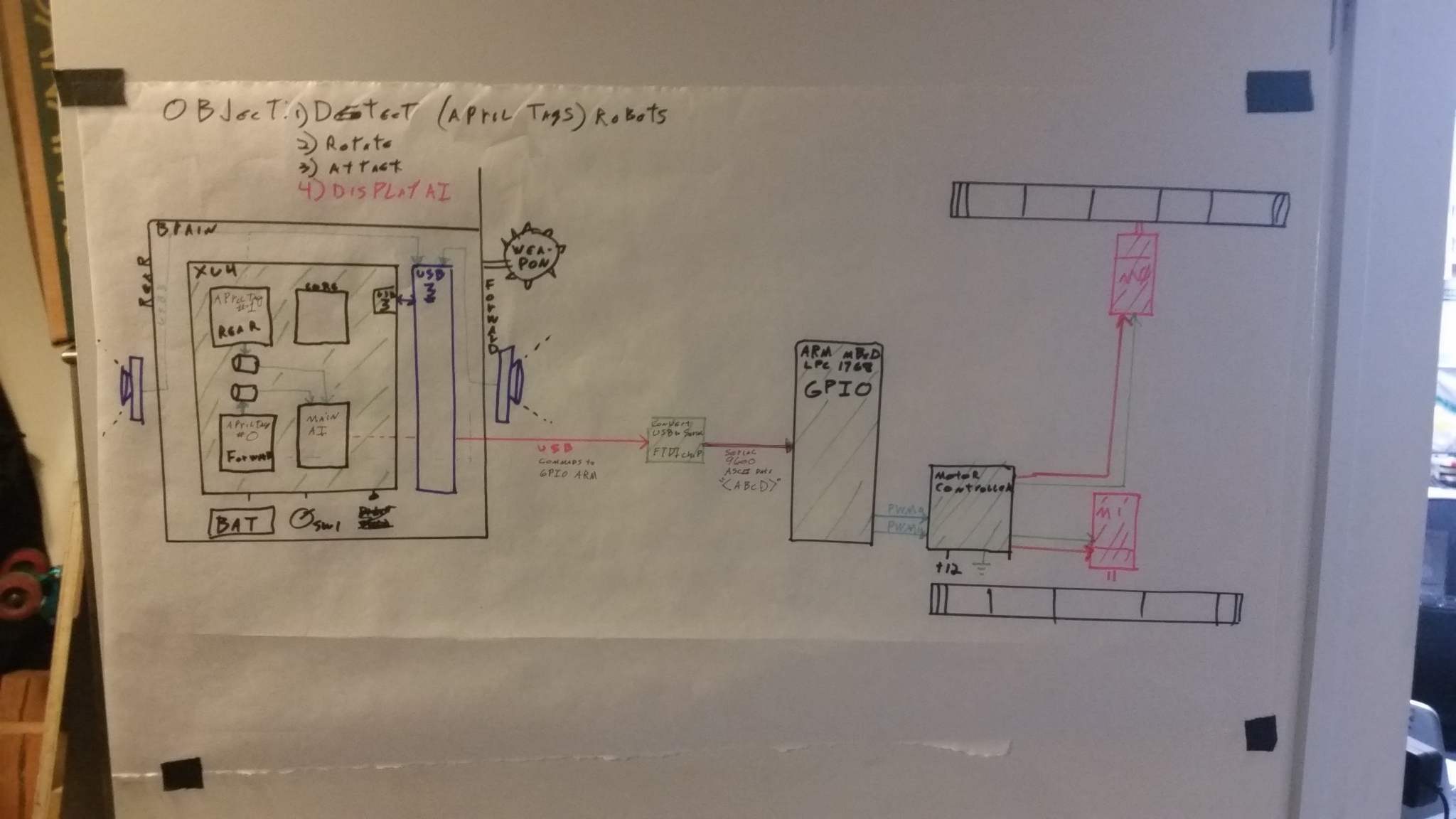

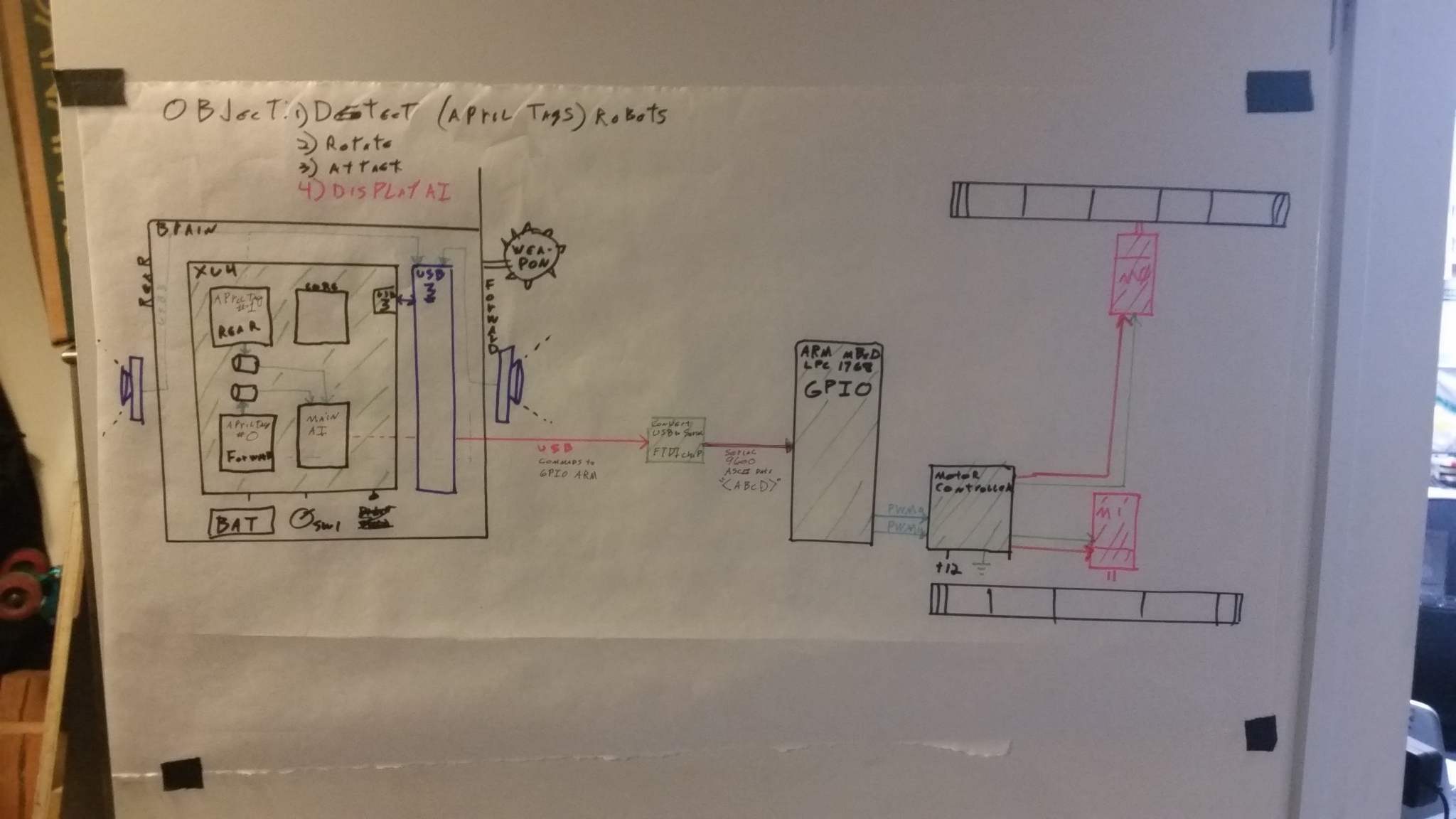

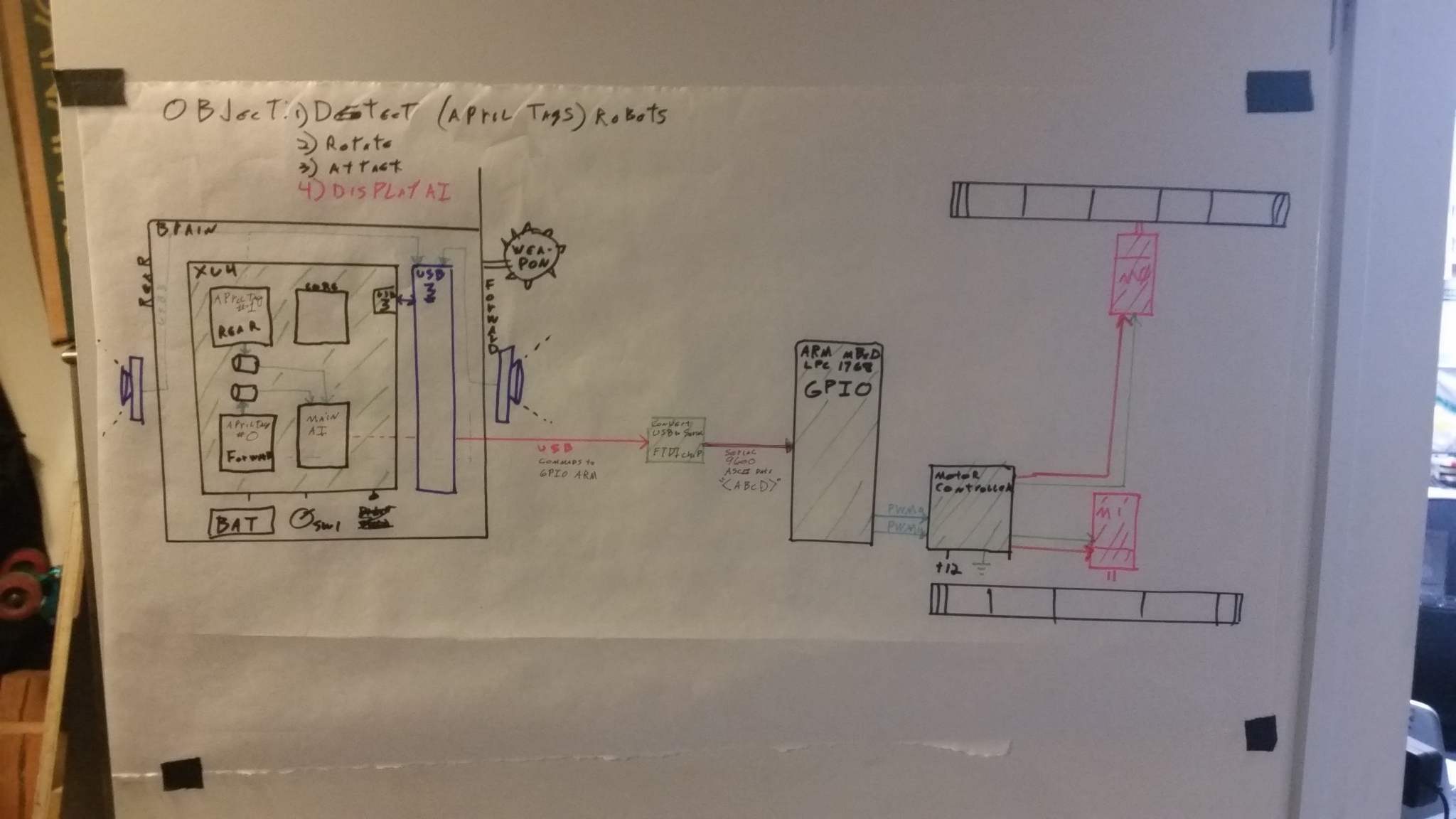

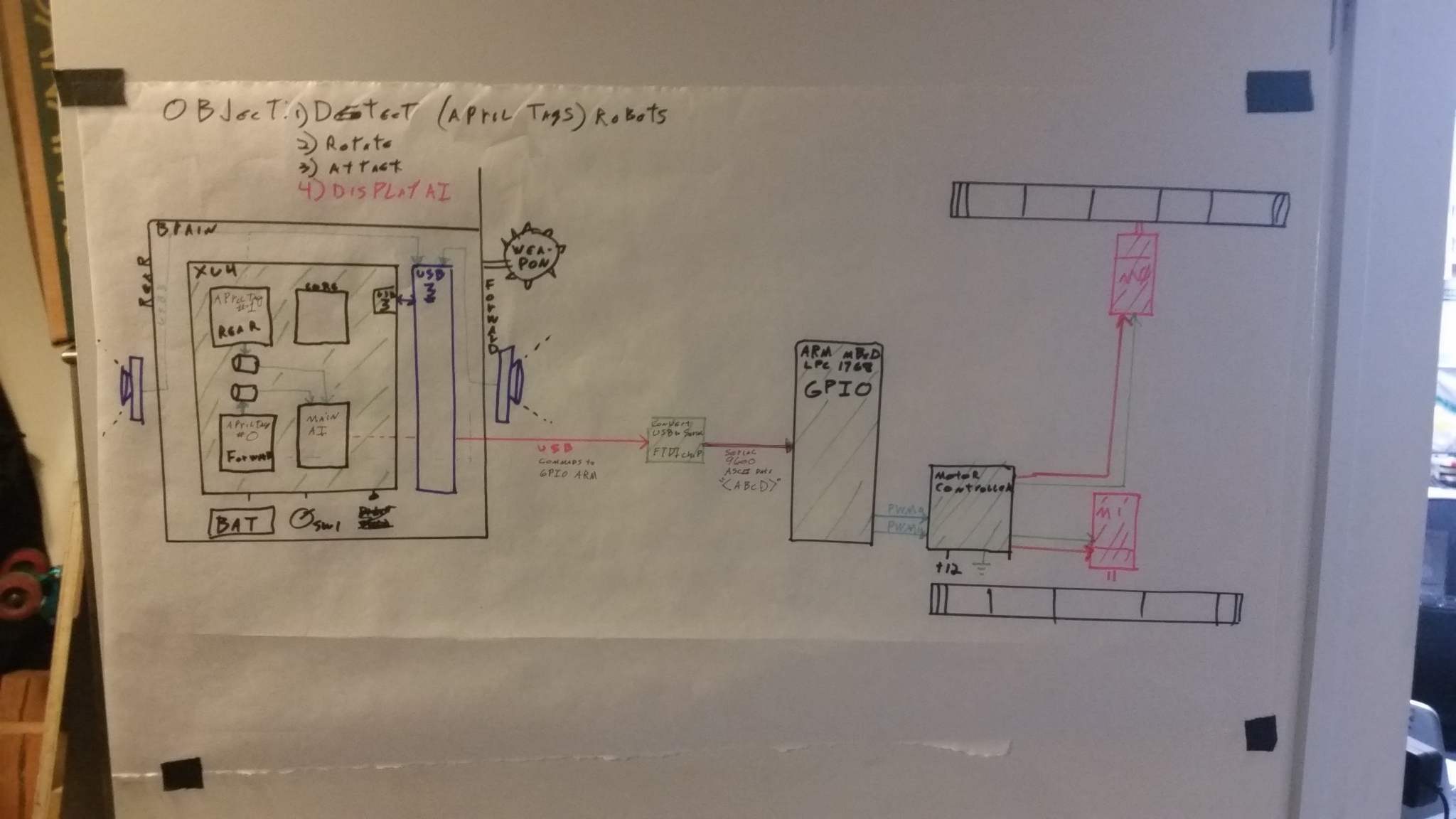

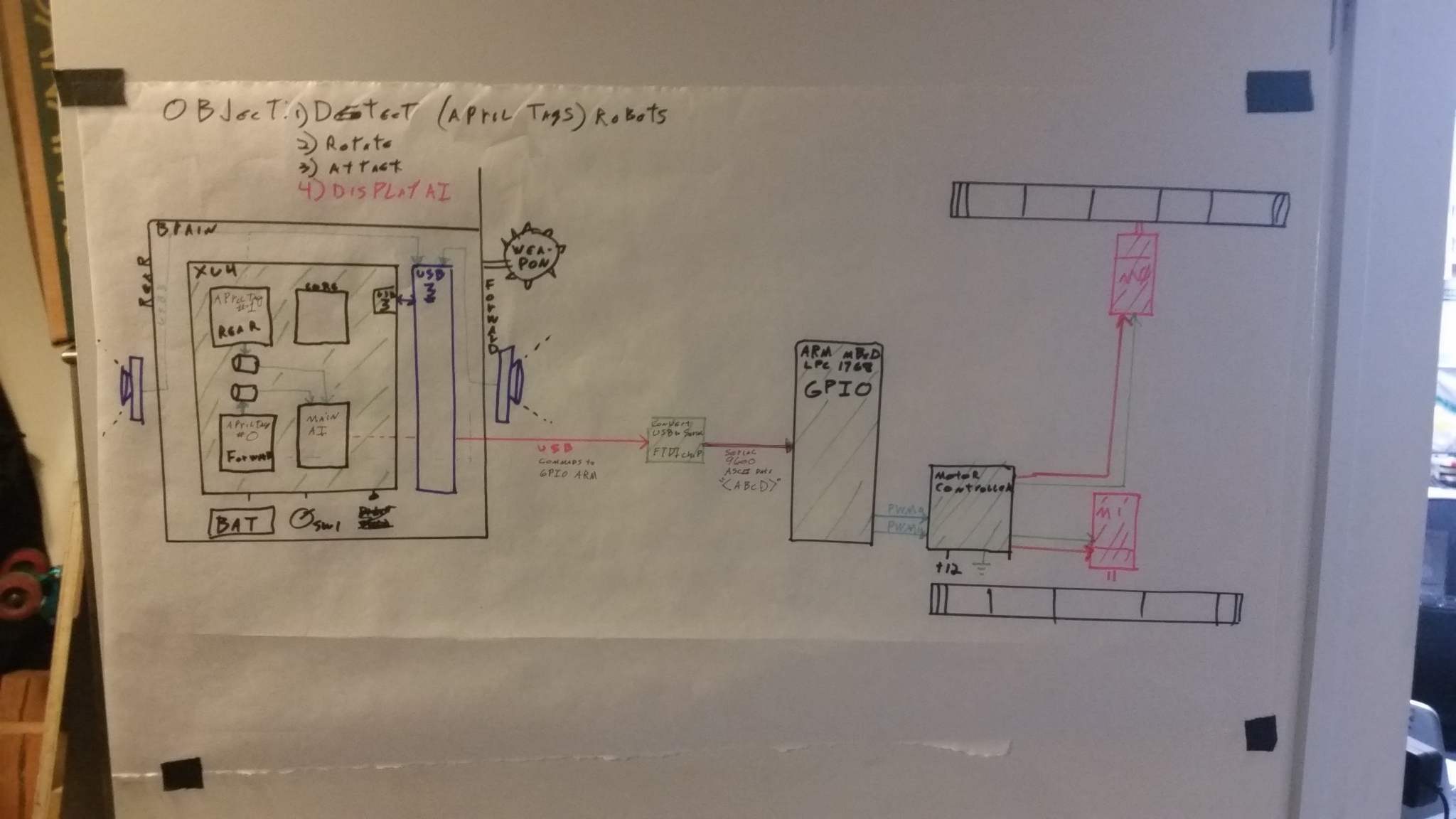

Mike decided on the hardware layout for the robot. His goal was simplicity. The less things you have on a robot, the less things there are to take. We decided to start with an Odroid XU4 as the primary control unit because we were both familiar with the platform. If you’re not familiar, think Raspberry Pi with more CPU cores, USB 3.0, and gigabit ethernet. This proved more than enough to get us running. That would be connected to a smaller microcontroller — an Mbed ARM chip. The ARM chip took commands from the XU4 and turned them into PWM signals for the motor controller. The Mbed platform is nice because it has a web-based GUI and programming it is as simple as connecting it to the USB port on your computer and dragging-and-dropping the binary file that the web compiler makes. We used a simple code to make debugging easy.

Pro tip: The signal between the XU4 and the ARM chip was letters, each representing one of the two motors. If you send “ZZ” through the wire, the car goes forward at full speed. If you send “zz” through the wire, the car goes backward at full speed. This is nice, because you can hook up a 7-segment display to the communication channel and see exactly what command is being sent at any given time.

We decided two on Logitech C920 Webcams for video feeds for the cameras, one on the front and one on the back. This is because we were working with limited bandwidth and the C920 supports video compression directly instead of having to do compression on the computer.

Treads coming together with custom mounts for the wheels

Treads coming together with custom mounts for the wheels

First prototype coming together

The actuators for the weapon are Dynamixel motors — very expensive but very precise. Mike had some laying around.

First prototype coming together

The actuators for the weapon are Dynamixel motors — very expensive but very precise. Mike had some laying around.

First test for the motor controller

Step two: Make the robot attack — and win (the hard part)

We need a way to get the robots to recognize each other easily. AprilTags served as a fantastic localization agent. AprilTags give you an approximate distance from and object as well as approximately how far they are away from you. The first problem we had with Apriltag detection was that it was slow. I decided to experiment with multithreading — maybe we could get two threads getting AprilTags detection running at the same time, or what if we could get two for the front and two for the back cameras all at once. We got good results with one thread running just the capture of the camera data and another thread running just the detection software. Here is me in my small San Jose studio at 11pm on a Friday getting statistics on single-threaded vs multi-threaded solutions.

Single threaded vs multi threaded:

Mike and I had a bet. If I could get multi-threading to work faster than the single thread, I would get a burrito.

Step 3: Getting the robot to defend

There are a lot of ways we could have done this that would have gotten better results, but, to be honest, we really wanted to use neural networks to control this robot because we were interested in neural networks and because that was a big hype word around then. By that time we had two people on the team, me and my buddy Max, who were familiar with reinforcement learning. Max made a simple simulator in unity to simulate two robots that could see how far away each other were. I then worked with him to train a reinforcement learning agent to decide when to go toward the other robot and when to go back, using the trained virtual robots against each other to try and get better. Once we got these virtual robots to the point where they exibited the behavior we wanted, we attached the neural network to the robot and watched it decide one of four things: “Move forward and attack”, “Move right”, “Move left”, or “Move back”. We were surprised at how well the robots actually made decisions — And they were vicious!

Step 4: Competition

After we got the robot running, we recruited more people. We got people from many backgrounds interested, including Berkeley Ph.D’s, people who had barely programmed but knew electronics, and Rocky, our Icelandic bodybuilder assistant and expert machinist.

Mike with our first arena in Berkekey

Mike with our first arena in Berkekey

Rocky made a holiday video

Make Magazine feature (“Father Daughter Duo” sounds better than “Plus some other guy”)

We were also featured on History Channel, which you can watch here. We’re about 3/4 of the way in.

Make Magazine feature (“Father Daughter Duo” sounds better than “Plus some other guy”)

We were also featured on History Channel, which you can watch here. We’re about 3/4 of the way in.